Science and Arts Exchange between China and the West

The European Palaces of Changchunyuan built by Qianlong in the early years of his reign marked the first introduction of European architecture and garden design into Chinese imperial residences. At the same time, under the impact of cultural exchange between China and the West, chinoiserie gardens, which incorporated Chinese designs, began to appear in European countries such as England and France while artworks with Asian aesthetics became highly popular.

Since the late-Ming dynasty, Western Jesuit missionaries began travelling to the East. In China during the 17th and 18th centuries, Qing emperors became especially interested in astronomy, mathematics and the mechanics of clocks and fountains. For instance, Emperor Qianlong ordered the Italian painter Castiglione and French missionaries Michel Benoist and Jean Denis Attiret to supervise the design; Ignatius Sichelbart to oversee the construction of waterworks, and Pierre Nicolas d’Incarville to administer greening in the gardens. From 1747 to 1783, these European palaces had been completed, integrating Chinese and Western styles, following the palatial structure of European Baroque architecture, while keeping Chinese elements such as white marble for impeccably carved reliefs and Chinese-coloured glaze tiles adorned with Western floral motifs for roofing.

Originally painted by Yi Lantai, European Palaces, copperplate print and image courtesy of the Poly Art Museum

Revelations from Chinese and Western Ancient Machinery

How did Yuanmingyuan’s water clock fountain operate before there was electricity? We could search for the answer within the inventions of ancient Chinese and Western machinery. The mechanical system of early European clocks could explain how the twelve bronze fountainheads of the Haiyantang zodiac fountain were able to spout water at different times of day; while the fountainheads were synchronised to simultaneously spout water at noon using the gnomon of the armillary sphere designed by Song dynasty scientist Su Song to tell the time.

At the same time, the hydro-mechanical astronomical clock tower, also designed by Su Song, featured humanity's earliest hydraulic stepper motors and escapement governors for mechanical clocks. Its steelyard clepsydra-controlled waterwheel relied on human power to run, and water rose gradually from low to high levels into the upper reservoir. This design was very suitable for the water lifting device in the Dashuifa.

The visitors can learn more about the water clock through three major inventions of ancient Chinese and Western machinery. The mechanical system of early European clocks explains how the 12 bronze fountainheads were able to spout water at different times of day; while the gnomon of the armillary sphere and hydro-mechanical astronomical clock tower, both designed by Song dynasty scientist Su Song, demonstrate how the fountainheads were synchronised to spout water at noon, along with the water lifting device.

Reconstructed in 2018

Aluminium alloy

Produced by the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology

On loan from Le Tandy International Limited

This model of a water transportation instrument is based on Su Song’s clock tower system, developed in the 11th century during the Northern Song period. The water instrument consists of a two-level noria device and a waterwheel steelyard-clepsydra device. As a closed circular water transportation system calibrated to measure equal units of time, it is the earliest known hydraulic stepper motor and escapement regulator for mechanical clocks in history. The waterwheel steelyard-clepsydra device, in particular, is unique to escapement regulators used for hydro-mechanical clocks in China. The two-level noria device relies on a helm driven by manpower to gradually lift water from low to high levels and eventually into the upper reservoir. As such, this design was particularly suited to the water-lifting devices used in the Dashuifa (Grand Fountain).

Reconstructed in 2018

Aluminium alloy

Produced by the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology

On loan from Le Tandy International Limited

Gnomons and armillary spheres are the two most important astronomical devices in calendar-making. This reconstruction of the armillary sphere created by the Northern-Song scientist Su Song exemplifies the shift towards maturity in the making of such devices in China. Su Song’s invention consists of a hollow sighting tube and three concentric rings, known as the Ring of the Six Cardinal Points (Liuheyi), the Ring of the Three Stellar Objects (Sanchenyi), and the Ring of the Four Movements (Siyouyi). In addition to measuring the position of celestial bodies along the equator, it can also be used together with a gnomon to calibrate time devices. In the case of the Yuanmingyuan (The Old Summer Palace), gnomons were used to ensure that all 12 zodiac bronze heads were synchronised to spout water simultaneously at noon every day.

Reconstructed in 2018

Iron, wood

Produced by the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology

On loan from Le Tandy International Limited

Early European mechanical tower clocks were powered by two weight-driven devices: the going train and the striking train. The going train system depends on the foliot and verge escapement regulator to measure time, whereas the striking train system uses the count wheel to regulate how many times the bell is struck. Furthermore, the striking trigger mechanism ensures that these two systems are connected, so that the bell is correctly struck – from 1 to 12 times – within the 12-hour system. This operative mechanism in early European tower clocks may help answer a frequently asked question regarding the Yuanmingyuan (The Old Summer Palace): How did the 12 zodiac bronze heads spout water at precise hours every day?

Gilt-brass Enamelled Singing Bird Clock with Automaton

France (ca. 1880)Metal, bronze, feather

On loan from a private collection

Clock in the Form of a Birdcage

19th centuryGold, bronze, feather

On loan from a private collection

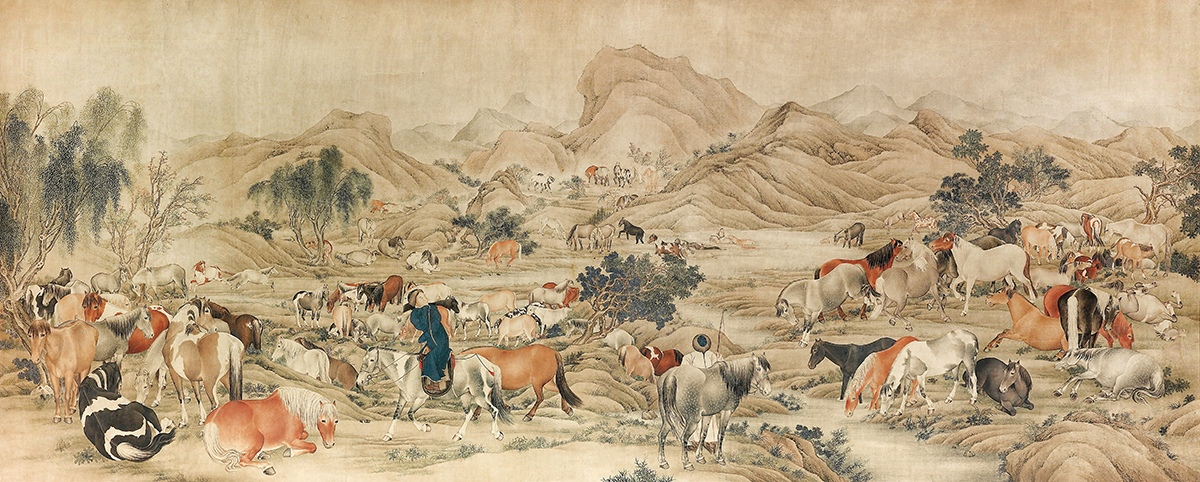

A Hundred Horses

AnonymousQing Dynasty (mid-19th century)

Colour on paper

On loan from the Art Museum, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Gift of Mr. Peter Chow, 1999.0035

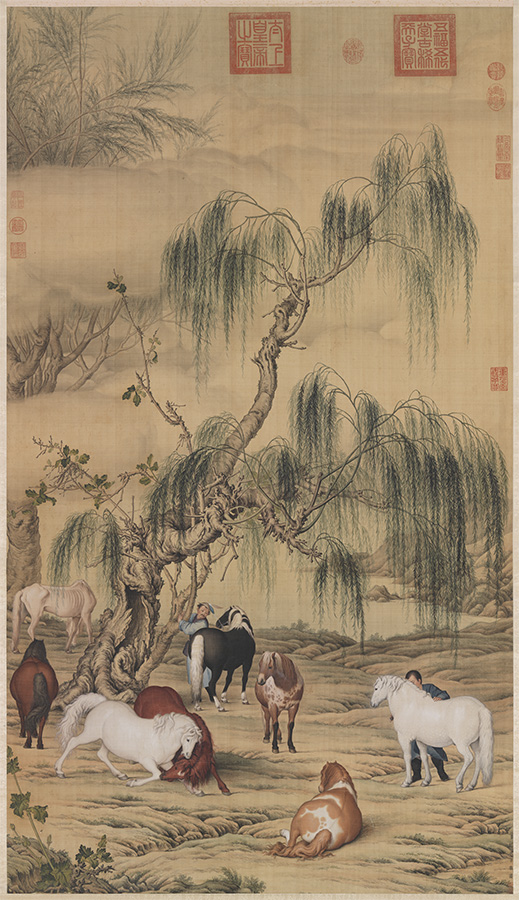

Eight Horses

Giuseppe Castiglione[Lang Shining] (1688 -1766)

Yongzheng Period, Qing Dynasty (1723 - 1735)

Ink and colours on silk,

facsimile

Gift from the Palace Museum, Taipei

Long-haired Dog Beneath Blossoms

Giuseppe Castiglione[Lang Shining] (1688 -1766)

Yongzheng Period, Qing Dynasty (1723 - 1735)

Ink and colours on silk,

facsimile

Gift from the Palace Museum, Taipei

Paired Cranes in Shade with Flowers

Giuseppe Castiglione[Lang Shining] (1688 -1766)

Yongzheng Period, Qing Dynasty (1723 - 1735)

Ink and colours on silk,

facsimile

Gift from the Palace Museum, Taipei

A Pair of Copper Cloisonné Enamel Roosters

Qianlong Period, Qing Dynasty (1736 - 1795)Copper, cloisonné enamel

On loan from the Poly Art Centre, Hong Kong

Painted Enamel Vase in a Double-gourd Shape with a Bird and Flower Design in Reserved Panels

Qianlong Period, Qing Dynasty (1736 - 1795)Metal, painted enamel

On loan from the Hong Kong Museum of Art

A Yellow-ground Floral Bowl in Famille Rose Enamel

Qianlong Period, Qing Dynasty (1736 - 1795)Porcelain, painted enamel

On loan from the Poly Art Centre, Hong Kong

A Yellow-ground Vase

Qianlong Period, Qing Dynasty (1736 - 1795)Porcelain, painted enamel

On loan from the Poly Art Centre, Hong Kong

Brush Holder with a Flower and Bird Design in Famille Rose Enamel

Late Tongzhi Period to Guangxu Period, Qing Dynasty (1873 - 1908)Jiangdezhen ware

On loan from the Art Museum, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2001.0444

Copper Vase with a Flower and Fruit Design in Painted Enamel

Qianlong Period, Qing Dynasty (1736 - 1795)Copper, painted enamel

On loan from the Art Museum, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Gift of Friends of the Art Museum, 1988.0053

Cup and Saucer with Crucifixion Design in Famille Rose Enamel

Qing Dynasty (ca. 1750)Porcelain

On loan from the Art Museum, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Gift of Friends of the Art Museum, 1996.0350

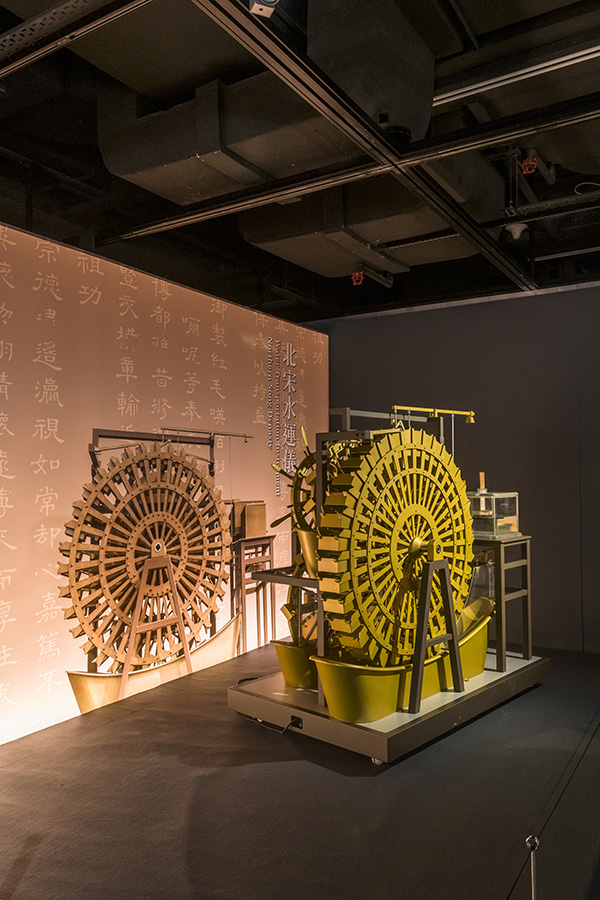

Replica Model of a Northern Song Dynasty Water Transportation Instrument

Originally made in the 3rd year of the Yuanyou era of the Northern Song Dynasty (1088)Reconstructed in 2018

Aluminium alloy

Produced by the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology

On loan from Le Tandy International Limited

This model of a water transportation instrument is based on Su Song’s clock tower system, developed in the 11th century during the Northern Song period. The water instrument consists of a two-level noria device and a waterwheel steelyard-clepsydra device. As a closed circular water transportation system calibrated to measure equal units of time, it is the earliest known hydraulic stepper motor and escapement regulator for mechanical clocks in history. The waterwheel steelyard-clepsydra device, in particular, is unique to escapement regulators used for hydro-mechanical clocks in China. The two-level noria device relies on a helm driven by manpower to gradually lift water from low to high levels and eventually into the upper reservoir. As such, this design was particularly suited to the water-lifting devices used in the Dashuifa (Grand Fountain).

Su Song's Armillary Sphere

Originally made in the 3rd year of the Yuanyou era of the Northern Song Dynasty (1088)Reconstructed in 2018

Aluminium alloy

Produced by the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology

On loan from Le Tandy International Limited

Gnomons and armillary spheres are the two most important astronomical devices in calendar-making. This reconstruction of the armillary sphere created by the Northern-Song scientist Su Song exemplifies the shift towards maturity in the making of such devices in China. Su Song’s invention consists of a hollow sighting tube and three concentric rings, known as the Ring of the Six Cardinal Points (Liuheyi), the Ring of the Three Stellar Objects (Sanchenyi), and the Ring of the Four Movements (Siyouyi). In addition to measuring the position of celestial bodies along the equator, it can also be used together with a gnomon to calibrate time devices. In the case of the Yuanmingyuan (The Old Summer Palace), gnomons were used to ensure that all 12 zodiac bronze heads were synchronised to spout water simultaneously at noon every day.

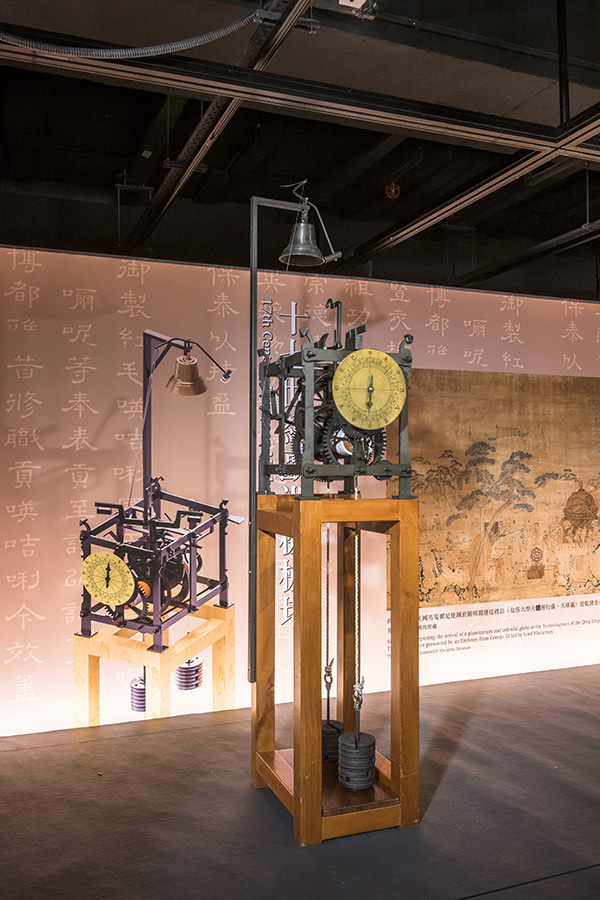

Early European Mechanical Turret Clock

Originally made in the early 17th century (1600–1650)Reconstructed in 2018

Iron, wood

Produced by the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology

On loan from Le Tandy International Limited

Early European mechanical tower clocks were powered by two weight-driven devices: the going train and the striking train. The going train system depends on the foliot and verge escapement regulator to measure time, whereas the striking train system uses the count wheel to regulate how many times the bell is struck. Furthermore, the striking trigger mechanism ensures that these two systems are connected, so that the bell is correctly struck – from 1 to 12 times – within the 12-hour system. This operative mechanism in early European tower clocks may help answer a frequently asked question regarding the Yuanmingyuan (The Old Summer Palace): How did the 12 zodiac bronze heads spout water at precise hours every day?