Our mission is to ensure the generation of accurate and precise findings.

Contact Us Ta-134/A, Gulshan Badda Link 61 383 766 284 [email protected]Surgical masks have been part of essential personal protection during the Covid-19 pandemic. However, the inappropriate disposal of surgical masks can cause serious microplastic pollution, equivalent to seriously polluting more than 54,800 Olympic-sized swimming pools of seawater annually, researchers from City University of Hong Kong (CityU) discovered. This can also affect the growth and reproduction of marine organisms and the food chain. The research team urged the public to dispose of their used masks properly and highlighted the importance of better environmental management, by formulating corresponding policies and law enforcement to ensure the proper disposal of surgical masks.

The research team was led by Dr Henry He Yuhe, Assistant Professor in CityU’s School of Energy and Environment (SEE) and a member of the State Key Laboratory of Marine Pollution (SKLMP). The findings were published in the academic journal Environmental Science and Technology Letters, titled “Release of Microplastics from Discarded Surgical Masks and Their Adverse Impacts on the Marine Copepod Tigriopus japonicus”.

Plastic material widely used in surgical masks

The research team cited an estimate by a US environmental protection organisation that global demand for surgical masks reached 129 billion per month by 2020. And some research estimated that owing to the lack of proper collection and management policies, 1.56 billion masks were inappropriately released into the ocean in 2020.

“Polypropylene (PP) is the main material widely used in surgical masks. It is a kind of commodity plastic that can break down under the effects of heat, wind, ultraviolet radiation, and ocean currents, eventually forming microplastics,” said Dr He. Microplastics are usually smaller than five millimetres and can take hundreds of years to degrade in the ocean.

A walk with his dog on a beach triggered Dr He’s interest conducting the research. “I saw one mask wedged between rocks on the shore and another floating on the water surface. Since all the masks are made of plastics and may be releasing microplastics, improperly discarded masks will affect the marine environment. I believe this problem will continue for many years in the post-pandemic era,” said Dr He.

To figure out the extent and magnitude of this pollution issue and its potential impact, Dr He and his team collected discarded masks from a beach in Hong Kong to investigate the release of microplastics from polypropylene surgical masks in seawater.

Seawater being polluted can fill more than 54,800 swimming pools annually

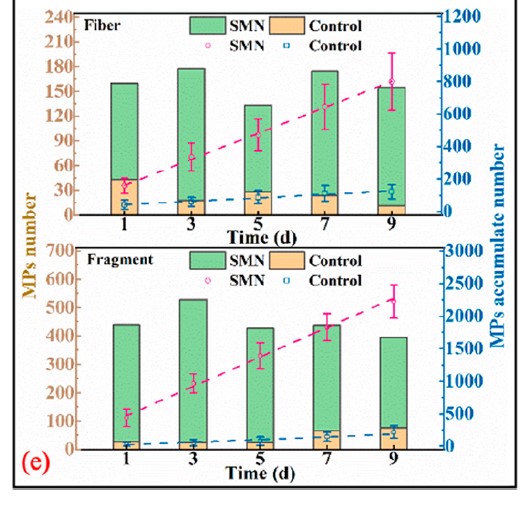

The team conducted experiments in the laboratory to mimic the natural process of microplastics being released from discarded masks. They soaked the masks in a bottle with artificial seawater and shook them continuously using a mechanical shaker for nine days. Under a microscope, they observed significant damage to the mask fibres.

After analysis, the team discovered that a mask weighing about three grams released about 3,000 microplastics. They estimated that 0.88 million to 1.17 million microplastics would be released during a mask’s complete decomposition.

Since about 1.56 billion masks ended up in the ocean in 2020, the team estimated that more than 1,370 trillion microplastics were released in the coastal marine environment from all the surgical masks improperly discarded during the year. “This amount of microplastics can seriously pollute 137 million cubic metres of seawater, which is equivalent to filling up more than 54,800 Olympic swimming pools,” added Dr He.

Microplastics accumulate in the food chain

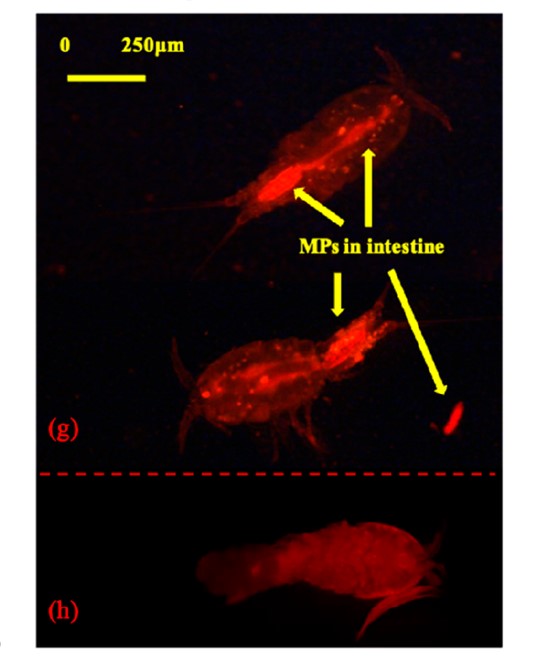

The team also evaluated the chronic toxicity of microplastics on copepods (Tigriopus japonicus), a small marine crustacean. In their experiment, the copepods were exposed to artificial seawater containing up to 100 microplastics per mL. The microplastics were ingested and accumulated in the intestines of the marine copepods. Compared to copepods not exposed to microplastics, the reproduction fecundity of those that were exposed to 100 microplastics per mL was reduced by up to 22%, and the maturation development time was 5.6% longer.

Dr He explained that as one of the most abundant classes of zooplankton and the main food source of other small animals in the marine environment, copepods play a critical role in the bioaccumulation of contaminants in the food chain. Microplastics can enter the bodies of higher-level marine organisms, such as fish and shrimps, if they consume copepods with microplastics accumulated in their bodies. The higher the animals are in the food chain, the more microplastics accumulate, resulting in potentially harmful effects.

In addition, the reduced fecundity of copepods can lead to a reduction in food resources for higher marine organisms, threatening the balance of the marine ecosystem.

Dr He pointed out that microplastics released from masks can also act as vectors for other pollutants, like plasticisers, in the marine environment and might have a cumulative effect on marine organisms.

The team believes that their research findings significantly demonstrate that the inappropriate disposal of surgical masks can have a long-term domino effect on coastal marine ecosystems, which requires more attention and further study. To minimise the risk of this emerging threat, better environmental management, policies and law enforcement are needed to ensure the proper disposal of surgical masks. The research team urges everyone to dispose of their used masks properly to prevent the pollution of microplastics in the marine ecosystem.

The corresponding author of the paper is Dr He. The first author is Sun Jiaji, PhD student, SEE and SKLMP. The collaborators are Professor Kenneth Leung Mei-yee, Chair Professor, Department of Chemistry and Director of SKLMP; Yang Shiyi, Master’s student, SEE and SKLMP; Dr Zhou Guangjie, Postdoc, SKLMP; Dr Zhang Kai, Postdoc, SKLMP; Lu Yichun, PhD student, SEE and SKLMP; Dr Jin Qianqian, Postdoc, SEE and SKLMP; and Professor Paul Lam Kwan-sing, former Director of SKLMP.

The research was supported by CityU and the Hong Kong Branch of the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Guangzhou).