The Age of Health Misinformation: From Pandemic to Infodemic

COVID-19 has sadly fuelled a torrent of false or misleading information that has complicated efforts to limit the spread of the virus

Social media has made misinformation about the pandemic both more accessible and far easier to spread.

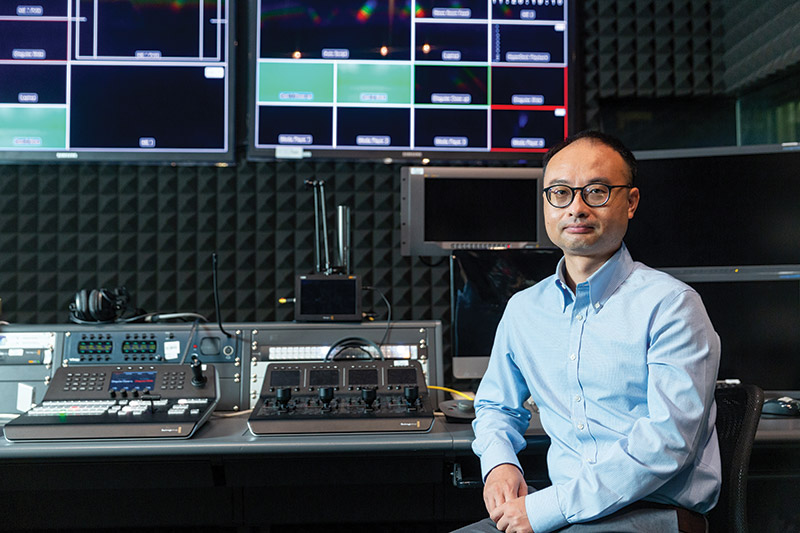

Dai notes how more voices in media are beginning to realise the importance of fact-checking in the fight against misinformation.

The world has been taken hostage by the coronavirus pandemic since late December 2019. In the years since, it did not only infect and kill but was also an unwitting accomplice to another relentless foe that entered our homes and lives as easily as the virus itself: misinformation.

Dr Chris SHEN, Associate Professor and Associate Head at City University of Hong Kong’s Department of Media and Communication says, “Misinformation is basically false or misleading information that is presented in news format. There are two key words here, one is ‘false’, describing the inaccuracy of the information; the second is ‘misleading’. Not all misinformation is intentionally trying to mislead—sometimes it’s a mistake that is avoidable. Disinformation, though, is clearly designed to sway people’s opinion in a certain direction.”

Shen explains that the contributing factors that help spread misinformation can be examined from two sides: the production side and the consumption side.

At the production side we ask ourselves the question: who is responsible for the emergence of misinformation?

“Both political and economic motivations can contribute to the production of misinformation,” says Shen. “There have been cases where countries can use social media to influence the politics of other countries.” In this he has alleged Russian interference in US elections in mind, for example. “A bigger contributing factor could be economic motivations, because misleading information really has a market out there.”

There is an attractiveness to misinformation, especially on social media where it can drive a lot of attention. “In an era of social media, attention means profits,” Shen says matter-of-factly.

Dr HUANG Guanxiong, an Assistant Professor (will be promoted to Associate Professor in July 2022) in the same department at CityU, says, “The spread of misinformation via both interpersonal and mass communication channels is not new. Nevertheless, the affordances of social media have accelerated the rampant spread of misinformation in several ways. First, social media enables users to publish unverified information and reach mass audience in real time. Second, social media enables users to actively engage with unverified information, thus triggering rapid spread through networks aimed specifically at increasing engagement. As a result, information that involves high public concern, regardless of whether it has been authenticated, tends to spread very quickly on social media.”

According to Shen, “There are many organisations and individuals who try to produce misinformation intentionally for the sole benefit of economic gains.”

But production without consumption is not a feasible business model. “There must be a reason that consumers are after these pieces of misinformation,” says Shen. Which means that the spread of misinformation has a psychological angle too.

“A lack of trustworthy information could sometimes drive people to misinformation and fake news,” Shen says. “A good example was during the early stage of the outbreak of COVID-19. In China a really large amount of health-related misinformation was shared on social media, which misled people into the wrong preventative behaviours.”

One of the studies conducted by Shen’s students found that people who have negative feelings during the pandemic are more susceptible to misinformation, as a result of a higher belief in that information.

He cites two examples, that drinking alcohol will stop people from getting ill, or keeping a piece of ginger in one’s mouth makes one invincible. “Along that line of reasoning, crisis and negative emotions could lead to people believing in misinformation.”

Falling into Bias Traps

This trend has been referred to as an “infodemic”, which the World Health Organisation defines as “too much information including false or misleading information in digital and physical environments during a disease outbreak”.

“Confirmation bias also plays a role,” Shen explains. “We are more inclined to believe information that fits our value system and which is consistent with our existing views.”

A lack of trustworthy information could sometimes drive people to misinformation and fake news

Dr Chris Shen

Huang concurs and puts contributing variables down to both individual factors and information factors. “For example, a piece of fake news that is highly relevant to the audience is more likely to be widely shared, like [that concerning] the COVID-19 vaccines. People who have insufficient knowledge on relevant topics may be more vulnerable to the influence of fake health news.”

Dr Nancy DAI is CityU’s Assistant Professor in the Department of Media and Communication, with a focus on personal perception and social influence processes in mediated environments and use of communication technology. According to her, “People don’t really like to spend that much time to process information, and they prefer what we call ‘positive heuristic’. For example, if they know the message comes from the [US] Centres for Disease Control, let’s say they think it’s a credible source—they just want to believe it. Because that gives them a conclusion that they need at that moment. That’s another reason people tend to carry a very strong confirmation bias when they process information.”

The role of the media in this context is a crucial one. “Journalists and fact-checking websites serve as gate-keepers whose duties include providing authenticated information, verifying information and correcting misinformation,” Huang says.

The Echo Chamber Effect

Before social media, all information went through a gatekeeper process controlled by traditional forms of media. Those were seen as an elite whose role was to keep track of information flow. But social media is more grassroots driven. Seemingly everyone can be a content creator these days but, crucially, without being subjected to any, or few, forms of verification and accountability. Dai has noted now that more and more of those new voices in media are starting to realise the importance of fact-checking and more researchers are entering the battle against misinformation by advocating media or news literacy. “I personally also teach about this in my class, so I guess these are positive sides to the battle. There are also many large social media service companies that are also devoting a lot of resources to developing courses to educate the general public about identifying misinformation.”

Simply labelling a piece of information as unverified significantly stops it from being spread to more individuals

Dr Nancy Dai

Facebook, for instance, has implemented a practice of labelling information as either verified or false. “That turned out to be one of the most effective strategies in terms of preventing misinformation from further spreading,” says Dai, though she notes that it can be very difficult to put a number on how people receive a correction message once exposed to false content.

The echo chamber effect is linked to the sentiment behind information bias. “We prefer information from people we trust, and through the pattern of social media connection it provides a natural setting for amplifying misinformation.” Shen reminds us that these networks are connected because they share similar views to begin with or are friends who use each other as input. “The pattern does not follow a random process. Like-minded people connect together and amplify this information.”

The consequences of the echo chamber effect are evident. Dai adds, “One of the negative consequences to that is it makes it less likely for someone to be exposed to messages that would challenge their existing beliefs. In the end, what they see reinforces what they believe. It becomes a vicious circle and information seekers become more and more narrow-minded in terms of consistently reinforcing what they believe.”

Fact-checking through Trusted Voices

One effective way to implement strategic communications lies in using and citing credible sources.

“This is a critical factor for people to evaluate the trustworthiness of the message,” Huang says. “It is important to adopt the view from authoritative sources and highlight the sources in the messages, which increases the believability of the messages.”

She adds, “Another way is to provide scientific evidence to support the view conveyed in the message. As COVID-19 related issues are highly relevant to people, they tend to process the relevant messages more thoroughly. The argument quality and the evidence are normally taken into consideration when they evaluate the believability of the messages. I suggest scientific evidence should be provided in an easy-to-digest, mobile-friendly way like infographics and short text.”

It is also important to improve tech literacy. Advances in technology have brought new ways to create misinformation. “Deep fakes are one of them,” says Dai. “They are much easier to spread because we are now in the era of Web 3.0. Nowadays, there is far more audience-generated information on the internet than information generated by professional content creators.”

This development makes it easier to spread information on social media platforms. Combined with the echo chamber effect, it makes for the potential for a perfect storm of misinformation. However, Dai also believes that new developments in technology could also lead to exciting opportunities for a return to greater credibility.

Ways to Combat Misinformation

What would that look like? From Dai’s perspective, there is no single solution, but research has revealed several helpful practices. One is to employ an empathetic stance even if there are opposing schools of thought. “If I confront somebody about his opposition’s position, that is likely to be met with something we call a psychological reactance. Essentially, people like to hold on to their existing beliefs; they don’t want to change, and they are not motivated to do so. One way to help mitigate the reactance is to construct your message in a non-demanding tone,” Dai shares.

It is recommended to carry out large-scale literacy education programmes to help the public increase their ability to discern misinformation

Dr Huang Guanxiong

Another is simply labelling information. “This practice is more relevant to social media platform companies,” Dai says. “Simply labelling a piece of information as unverified significantly stops it from being spread to more individuals.”

Huang is also optimistic: “There are several possible solutions to this issue. First, governments can impose regulations to penalise people who deliberately create and spread fake news with malicious intent.”

“Second, professional fact-checking services can be provided to the general public to correct fake news in a timely manner,” she says. This is a point Shen reinforces, “There is a large amount of research out there demonstrating the effectiveness of fact-checking in terms of reducing the negative effects of misinformation.”

Huang’s third potential solution involves artificial intelligence. “Social media platforms have utilised AI-driven technologies to identify suspicious posts and take proper actions such as removing or tagging the posts that may contain misinformation.

“Last but not least, it is recommended to carry out large-scale literacy education programmes to help the public increase their ability to discern misinformation.”

Clearly the issue of misinformation is complex and only more fraught when it involves a topic like healthcare, so a multi-pronged approach is necessary. As Shen says: “A divided society will foster misinformation, so it is very important to build trust in society, in health authorities and scientists. In an information-rich environment, it is very easy for people to receive different information from diverse sources. And we need to build trust in the public, especially toward authorities in the scientific research communities. That is important.”