EMI Research Generates Social Impacts in Healthcare and Secondary Education

As CityU’s Assistant Professor in the Department of English, Dr Jack Pun’s research into English as the medium of instruction has implications for fields such as healthcare as well as for academics

Pun went through the entire education system in Hong Kong. His experience of overcoming language barriers motivated him to enter the research field of English as a medium of instruction (EMI).

Born and raised in Hong Kong, Dr Jack PUN completed his schooling and ordinary degree in the city before he went on to do a PhD in Education at the University of Oxford, UK, specifically in Applied Linguistics and Science Education.

Today, Pun is an Assistant Professor in the Department of English at City University of Hong Kong. His work within the field of Applied Linguistics has led to his primary interests in English as medium of instruction (EMI), English language education, second language acquisition, sociolinguistics and Systemic Functional Linguistics. Pun is particularly interested in studying classroom interactions regarding EMI, and the academic literacy and language challenges exposed to the students by use of varying EMI instructions.

“I went through the entire education system in Hong Kong, learning from Chinese medium instruction to English medium instruction,” he says. “When I moved to university, I encountered such a language challenge when switching from Chinese platforms to English. Imagine that—all of a sudden everything turned into English.”

Majoring in Chemical Technology with a minor in English at his undergraduate years, he encountered enormous challenges when it came to the use of a language (English) that was not his mother tongue, especially on the science subjects. Although he was suddenly faced with this difficult barrier, Pun says it also served as his motivation.

The experience became the catalyst for Pun to enter the research field of language education and health communication. His interest was borne out of a sense of empathy as Pun questioned whether there was anything within the realm of education that could help students like him, living in Hong Kong with limited English proficiency.

“That’s why when I graduated from my chemistry degree, I moved to the English department to sort of apply what I learnt from various scientific approaches in order to understand language,” Pun says. He moved on to study a Master’s degree in English Language Studies, before eventually enrolling in his doctorate at University of Oxford.

Learning in a Linguistic Melting Pot

As part of his PhD, Pun visited around 30 secondary schools in Hong Kong—all provided access to their science classrooms. “Thanks to those local schools, I’m particularly fortunate to have this opportunity to learn how science is being taught. During my visit, I’m interested in looking at how some teachers teach science with the medium of instruction being English.” The scholar ended up interviewing science teachers and students on their language challenges. Interestingly, he found that the secondary schools all claim they use EMI, but in fact have different ways of implementing EMI and use of the English language to cater diversified students’ English backgrounds. Some classes do “code-switching” between Cantonese and English.

This finding would shape Pun’s ongoing research, one of the projects he is undertaking with the Quality Education Fund (QEF). “I am trying to develop some pedagogical tools—in particular looking at writing—to enhance the teaching methods of science teachers in terms of scientific writing.”

One such tool recommended by Pun is the process of “translanguaging” in teaching. This is to incorporate the students’ first language into the lessons for it to act as a bridge towards their English learning experience.

In addition, Pun and his team has sought to apply a genre-based pedagogical approach to enhance local secondary school students’ English writing ability in science subjects. They conducted a 12-week writing workshop with nine local secondary schools where students were taught to write scientific reports based on common lexico-grammatical features. Which are often found in scientific writing. This comes alongside learning activities designed to help them write effective and accurate scientific texts. A website with resources has been developed for promoting effective scientific writing (https://www.teachingscienceenglish.com).

“By recording interactions between teachers and students, through this authentic data, I can come up with pedagogical solutions or suggestions of effective ways of implementing EMI instruction in science classrooms,” Pun explains. As the Assistant Professor points out, his research suggests that there is a lot of switching back and forth between Cantonese and English. “We need to prepare teachers and students with suitable pedagogy in order to maximise the learning outcomes of these EMI classrooms. It is a very challenging issue; that’s why in the current situation, a different school or even a different teacher, they have different interpretations of their preferred medium of instruction.”

Because we live in this multicultural society, with different languages, cultures and also different areas, our health is all tied together

Dr Jack Pun

Building a Communication Framework for Doctors

Pun’s research has benefitted not only teachers and students, but it has far-reaching impact on healthcare experts as well. As a bilingual speaker of Chinese and English, Pun is motivated to investigate health communication from a cross-cultural and cross-disciplinary perspective.

This was evident in one of his research projects where he found discrepancies in efficiency between how two different shifts medical co-workers interacted, but also how these healthcare professionals interacted with their patients and vice versa.

“In this one research, we were looking at how clinicians interact with each other and with patients, and among other health professionals.”

Pun recounts a project of 10 years ago that he embarked on with Professor Diana SLADE from the Australian National University (ANU), Director of the ANU Institute for Communication in Health Care. The research looked at how doctors in an emergency room communicate with their patients. “We found that because of the nature of the emergency department, everything needed to be quick, to be focused on patient safety regarding medication—so there is a lot less focus on interpersonal aspects.”

“We came up with a communication framework trying to help junior doctors who are starting their journey in the emergency room on how to improve their communication with the patients including a balance between medical and interpersonal components.”

To-date, little work has been done to research the best communication models for healthcare providers in Hong Kong. When medical doctors are trained in EMI environment, learning clinical communication skills who were developed from the English-speaking world, significant sociocultural differences may exist and lead to differences in healthcare delivery and communication. “We need to develop a specific culturally appropriate model of clinical communication which can provide better relationships between clinicians and patients,” Pun says. Pun has conducted various presentations on clinical communication for medical doctors in Hong Kong and worldwide, one of which was presented to 30 future oncologists at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. The emphasis was on clinician-patient communication in East Asia, followed by a discussion on the cultural aspect of implementing the well-known approach to teaching and training clinical communication skills in Asia—The Calgary-Cambridge Guide.

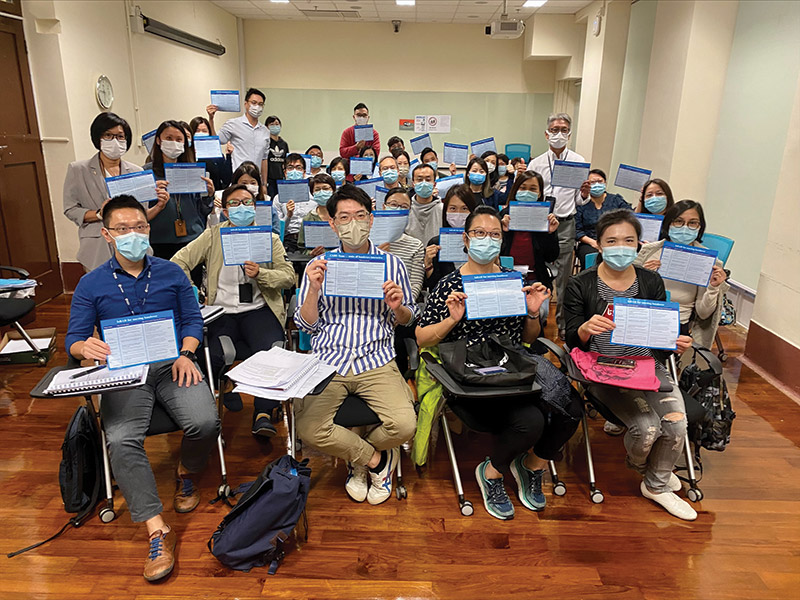

Besides, Pun has worked collaboratively with local public and private hospitals in promoting effective nursing handover training. Recently he launched a simulation training for local nurses on how to effectively handover their nursing duties. Working with his collaborator from Australia and team in Hong Kong, he also presented two common protocols for effective nursing handovers—the ISBAR (Identify, Situation, Background, Assessment and Actions, and Recommendations and Readback) protocol and the CARE-Team (Connect, Ask, Readback, and Engage) framework. A website with resources has been built for promoting effective nursing handovers (https://www.nursinghandover.com).

Together with the Hospital Authority and local hospitals, Pun and his team have developed training materials to enhance local nurses’ clinical handover and communication skills, an ongoing project entitled “Building Effective Nursing Clinical Handover Communication: Improving Patient Safety”. It was open for participation for 600 nurses in Hong Kong in a four-hour training programme.

His research does not only benefit nurses, but also other healthcare workers. His qualitative research workshop conducted with the Hospital Authority New Territories West Cluster aimed to train 23 healthcare staff to conduct qualitative research using a computer software called NVivo.

Such programmes have far-reaching impact on social changes not only for veteran healthcare workers but also for a new generation of medical students.

The Benefits of Inter-Departmental Connections

At CityU, Pun gives credit to the university’s strategic plan which looks at the priorities of their research, one of which is a theme called: “One Health”.

The idea is about the interconnectedness of different disciplines or the various branches within the same discipline and how they all interact and affect one another. Pun’s research is reflective of CityU’s strategic research theme in which his findings and programmes that—seemingly—are geared to one, actually benefit all.

“We are seeing how the impact is not on an individual level but as a society on a community level. Because we live in this multicultural society, with different languages, cultures and also different areas, our health is all tied together.”

The impact of Pun’s pedagogical approach has already borne results in healthcare and educational institutions in Hong Kong, and will surely continue to affect the future of educators and healthcare workers in the city and beyond.