EXHIBITION

展 覽

展 覽

- About the Exhibition

關於展覽 - Cabinets of Curiosities Sections

「藏珍閣」章節

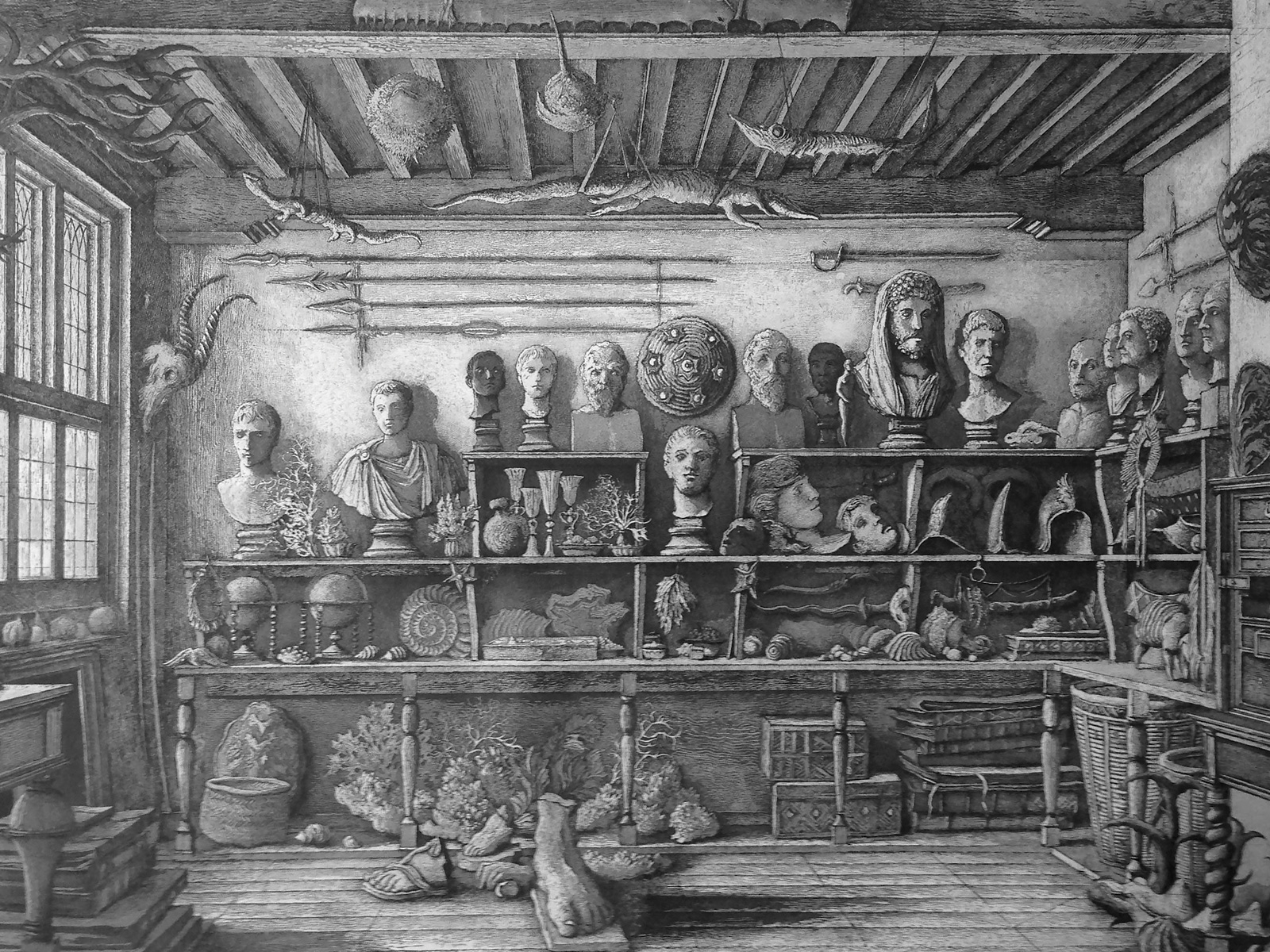

- Section I:

Cabinets of Curiosities – A Brief History

「藏珍閣」─ 簡史 - Section II:

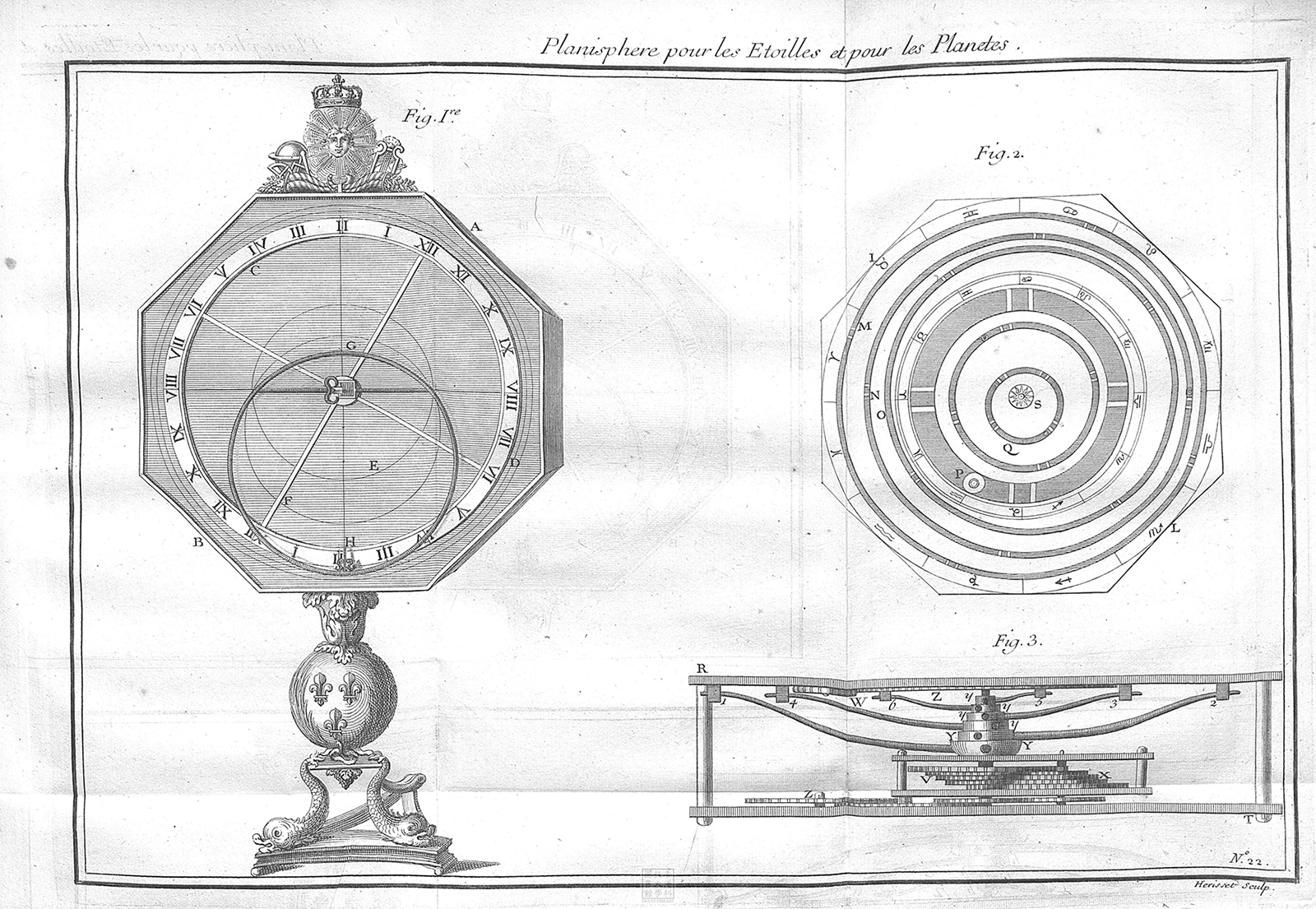

Maritime Expeditions and the Collecting of Exotica

航海探險與奇異珍藏 - Section III:

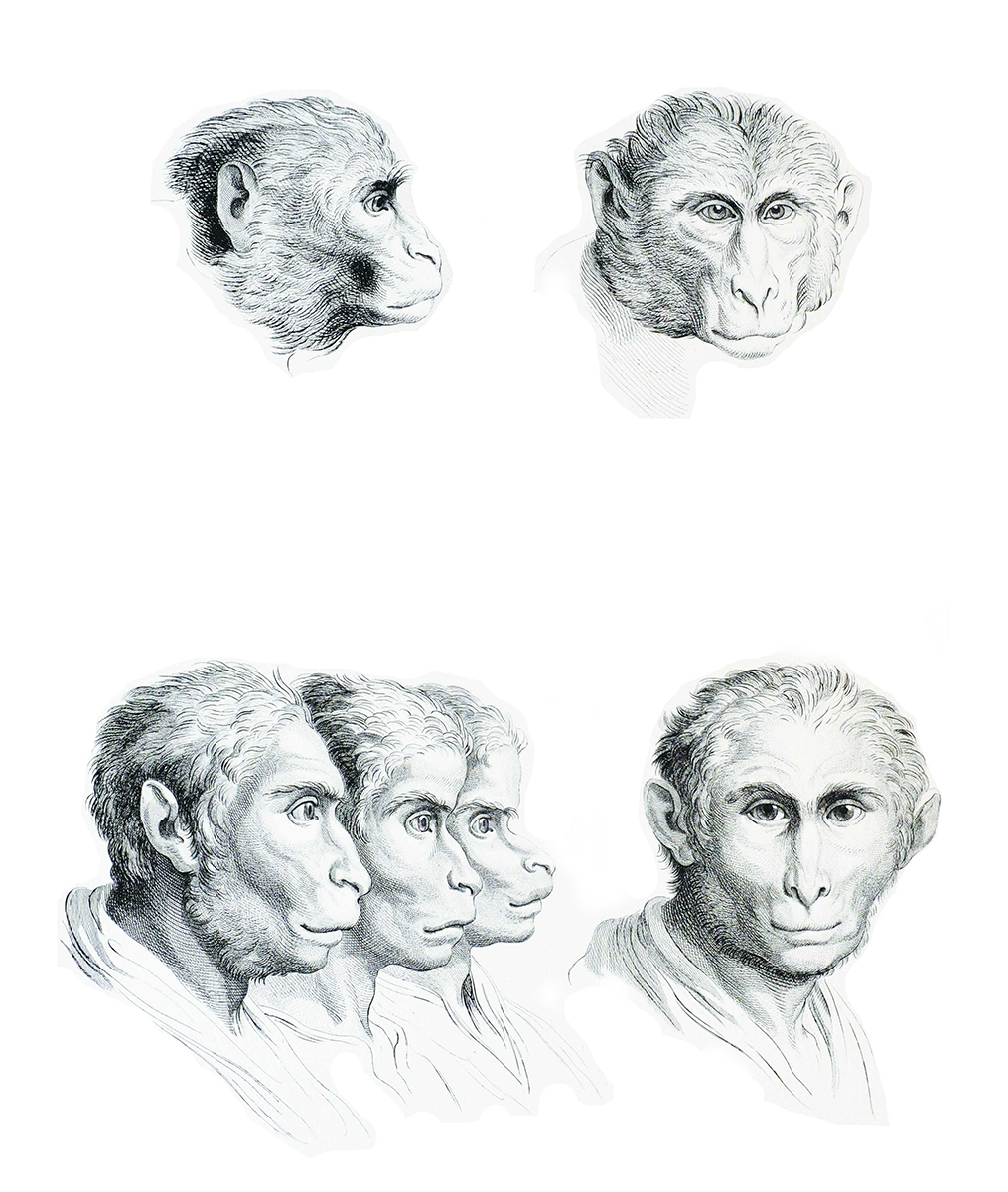

The Musée du Vivant – AgroParisTech: From Amateur Collections to

Discoveries in the Natural

巴黎高科農業學院生命科學博物館:從業餘珍藏到自然科學探索 - Section IV:

The Maison Deyrolle Cabinet of Curiosities: Nature Art Education

戴羅勒標本屋的「藏珍閣」:自然、藝術、教育 - Section V:

Cabinets of Curiosities and Contemporary art

藏珍閣與當代藝術

- Curators

共同策展人 - Credits

鳴謝