Automatic Text Simplification: A Breakthrough Innovation

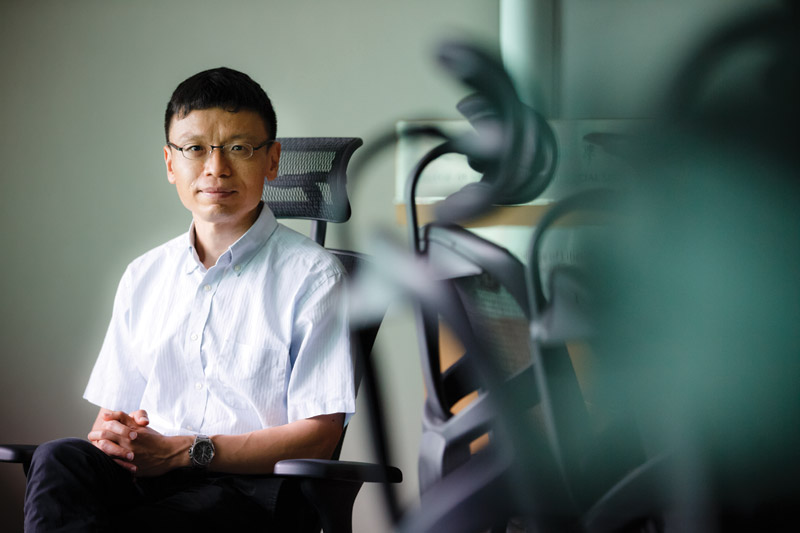

Dr John LEE Sie-yuen explains his new research project on automatic text simplification and its real-world applicationsBy securing a US patent to crown his latest research project on an algorithm for automatic text simplification, Dr John LEE Sie-yuen, Associate Professor at CityU’s Department of Linguistics and Translation, has shown the study of language from a computational perspective can lead to a breakthrough innovation with a range of potential applications.

In essence, his invention makes it possible to take a text an individual may find difficult, perhaps a legal document or a Wall Street Journal editorial on economic policy, and creates an easier to understand version.

It does this by adjusting the original vocabulary and syntactic structure, using word replacement and shorter sentences, to bring out the meaning for non-experts in the subject or those still learning the language.

Crucially, the process can also be customised, anticipating the words and level of complexity each reader can already handle and, as a result, only simplifying as much as necessary.

In effect, it takes account of education, professional background and language proficiency, improving on the conventional approach which tends just to throw up the most basic synonyms, whatever the context, or changes too little, thus leaving the reader still unenlightened.

Identification and Simplification

“While many text simplification algorithms have been designed, to the best of my knowledge, this is the first one that is personalised,” says Lee. “That is the innovation in the patent. In principle, you can input any text – English, Chinese or whatever – and the computer will simplify more for, say, a Grade 1 student and less for Grade 12.”

To personalise, it makes use of a process called complex word identification, a predictive model which needs some training data to get things started. That comes from giving the intended user 50 sample words to indicate with a yes or no answer which of them he or she knows. The words represent different levels of difficulty and frequencies of usage. With this information, the computer can then predict which other words the user would understand in that language.

Taking English as an example, Lee explains that the 50 sample words are carefully chosen and the same for every person. When picking them, his research assistants referred to Education Bureau guidelines on what students are expected to know in various grades and checked readily available sources on word frequencies in newspapers and other publications.

On an ascending scale covering five levels of difficulty, test words might be, for example, “boy”, “room”, “technology”, “comprehension” and “parataxis”. Taking your answers, the model can predict what else you know and, therefore, which words in a text will need simplification.

Doing that involves two stages: first syntactical, to break up long sentences, and then lexical, or word replacement. That is where the personalised aspect kicks in, deciding which words to substitute given the model’s knowledge and predictions.

“It would decide, for example, that for a linguist the word ‘parataxis’ is OK,” Lee says. “But if a word does need to be simplified, the model will search for synonyms that fit the context, are semantically most similar, and are known to the reader. If a system is constrained to use only very simple words, it is hard to be faithful to the original reading. With this model, you can consider who the reader is and make the trade-off, so as to choose the best synonym.”

We have ever more text that has been digitised and can be manipulated by computers. It is a golden era for using statistical methods to analyse language

Dr John Lee Sie-yuen

Harnessing the Power of Technology

Lee traces his initial interest in this field of research back to his high school years in Toronto. As part of a Grade 11 computer course, he was asked to do a relevant term project. He was also studying French at the time, so decided to write a program in Basic to conjugate regular French verbs automatically.

“I thought it was one problem a computer could solve, and it was my first attempt to apply computer science to language processing,” he says, noting that it ultimately led to a PhD in computational linguistics at MIT. “Language technology is increasingly a big data field because we have ever more text that has been digitised and can be manipulated by computers. It is a golden era for using statistical methods to analyse language.”

The latest project was supported by an Innovation and Technology Commission grant and, so far, has taken about 18 months. Work is continuing on some refinements to the prototype system to enhance the modelling of vocabulary and complex word identification.

“We are also hoping to apply neural networks and other artificial intelligence technologies before offering it to the public,” Lee says. “Another research question that still needs work is deciding which words cannot be simplified, and should instead be glossed. And, rather than asking the user to indicate his or her knowledge of 50 sample words, the better way might be to collect feedback as the user reads documents with the system. With ongoing feedback, the model’s prediction will become more accurate and the simplification more tailored to your level.”

Several possible applications are already being discussed. For instance, it could help teachers prepare materials for the classroom. Publishers may want to offer different versions of a book for readers with different language abilities. And search engine results could be improved by selecting options most suitable for the reader’s language proficiency level.

“Looking ahead, a potential research direction is to use text simplification in reverse to propose better vocabulary choice for formal writing,” Lee says. “For instance, you put in your essay and the system can spot vague, generic words and suggest harder but more precise words as replacements.”