Dickens and the City – capturing the urban experience

By : Michael Gibb

Consider CityU’s location. A walk from campus through the local communities takes you through an array of differing cityscapes. You’ll encounter low-rises with well-tended lawns, public estates, notable schools and historic churches, narrow lanes and vast concrete highways.

Such a walk can inspire the imagination and create a greater sense of place.

“The city has always been a source of inspiration for writers who want to capture, as well as re-imagine, the cityscape and the urban experience,” says Dr Klaudia Lee Hiu-yen, Associate Professor and Head, Department of English (EN), whose research areas include nineteenth-century literature and culture, narrative theory, spatiality, comparative and world literature.

One of her courses on the BA English programme in EN, “Literature and the City,” encourages students to walk the streets of Hong Kong, observe, remember, reflect and then write about their experience. Students draw on theories and critical perspectives in cultural and literary studies, urban studies, sociology and philosophy of place to explore ideas about the city, such as those related to modernity, sites of memory, cosmopolitanism, and spaces of power.

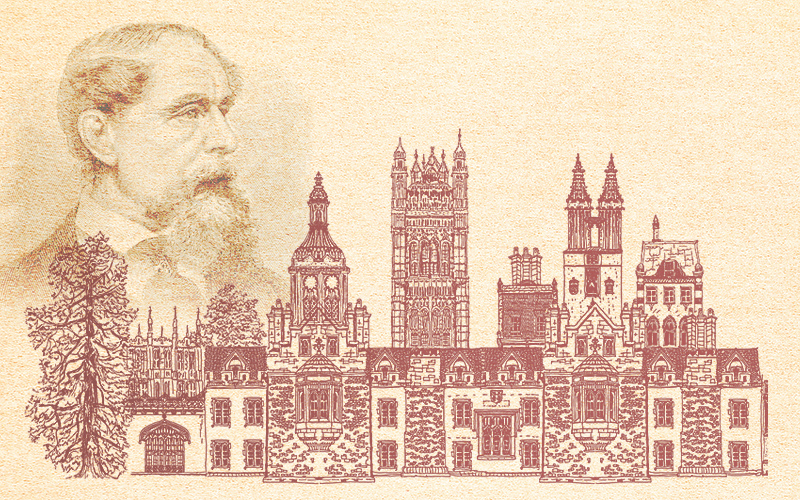

The recommended texts include local writers whose works are inspired by the Hong Kong urban environment as well as Charles Dickens, whose works Dr Lee specialises in. She uses one of Dickens’ works, a piece of literary journalism called “Night Walks” about an insomniac (author-narrator) who walks the streets of London at night, to encourage students to consider their own city streets.

The recommended texts include local writers whose works are inspired by the Hong Kong urban environment as well as Charles Dickens, whose works Dr Lee specialises in. She uses one of Dickens’ works, a piece of literary journalism called “Night Walks” about an insomniac (author-narrator) who walks the streets of London at night, to encourage students to consider their own city streets.

She notes Dickens wrote extensively about the relationship of the individual with urban development. “Dickens showed in his novel Dombey and Sons how some people in the city reacted with fear and some with hope at the impact of new railway lines on cities,” Dr Lee says.

Despite his books’ size—like many nineteenth-century novels, they can run to around 900 pages – Dickens is rewarding. His timeless stories are filled with legendary creations, from Fagin and Oliver Twist to Scrooge and David Copperfield, and he highlighted the dire poverty and living conditions that the poor experienced, always siding with the disadvantaged.

Not only that, Dickens’ works have regularly been adapted and performed, as well as taught, in Hong Kong, Dr Lee says.

“Some notable adaptations performed or screened in Hong Kong include a 1992 theatrical adaptation of Great Expectations that drew on Hong Kong’s colonial history and a 1955 film adaptation in Chinese called An Orphan’s Tragedy, which was an adaption of that same novel,” she says.

“Some notable adaptations performed or screened in Hong Kong include a 1992 theatrical adaptation of Great Expectations that drew on Hong Kong’s colonial history and a 1955 film adaptation in Chinese called An Orphan’s Tragedy, which was an adaption of that same novel,” she says.

Another recent adaption of Great Expectations performed in Cantonese in April at Hong Kong City Hall coincided with a major international symposium at CityU on Charles Dickens organised by Dr Lee.

“The new adaption of Great Expectations was a good opportunity to bring literary scholars and theatre and adaptation practitioners together to discuss different critical and creative engagements with Dickens’ novels and dramatic works,” she says. “Our symposium highlighted the creative processes involved in adapting and translating the work for theatre in the city.”